Oxford, Bodleian MS. Kennicott 1

- Details

- Item Images (3)

- Graphic Elements (3)

- Specimens (3)

Details

Oxford, Bodleian MS. Kennicott 1

Kennicott Bible

Bodleian Library (Oxford, United Kingdom)

Item Nature

Codex

Writing

Parchment

Brown (iron-gall)

Calamus

Ruling

There is ruling

Hard point

Grid of single vertical and horizontal lines

30

Date

וסיימתי אותו ביום רביעי א"ב ימים לחדש אב שנת והביאותים א"ל ה"ר קדשי לפרט האלף הששי

August 1/2, 1476

Place

La Coruña, Spain

מתא לה קורוניא

Sepharad

Language

Hebrew

Subject Field

- Bible

- Linguistics

Vowels and Signs

Complete

Tiberian

Other

http://bav.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/news/the-kennicott-bible

In June 1770 Benjamin Kennicott, biblical scholar and Librarian of Oxford’s Radcliffe Library, told the Radcliffe trustees that ‘it might add considerably to the Ornament of that Library, if it possessed one manuscript of the Hebrew Bible’. He informed them that he had in his hands such a manuscript, ‘very elegant and finely illuminated’, and that it was for sale. The trustees duly purchased the Bible the following April, and it remained the property of the Radcliffe Library until 1872, when it was transferred to the Bodleian. Kennicott could not have made a better choice, for the Bible, now named after him, is one of the finest Hebrew manuscripts in existence. How did he come by it? It had been placed in his hands by the Earl of Panmure, to whom it had been entrusted by its owner, Patrick Chalmers, a Scottish merchant, who had purchased it in Gibraltar. From Gibraltar we can trace the manuscript back to north Africa, and from there to La Coruña in Spain, where it was created.

Our witness is the scribe, who in a colophon at the end of the biblical text signed his name, Moses Ibn Zabarah. He recorded that he finished the work in La Coruña in the 5236th year since the Creation – that is, AD 1476; that he was responsible for copying, checking and correcting the entire text; and that it was made for his patron, the ‘admirable youth, Isaac, son of the late honourable and beloved Don Solomon di Braga’:

The blessed Lord grant that he study it, he and his children and his children’s children throughout all generations … And God enable him to produce many books, in order to fulfil the saying ‘and moreover take care, my son, to produce many books, books without end’. Amen, God grant that it be so.

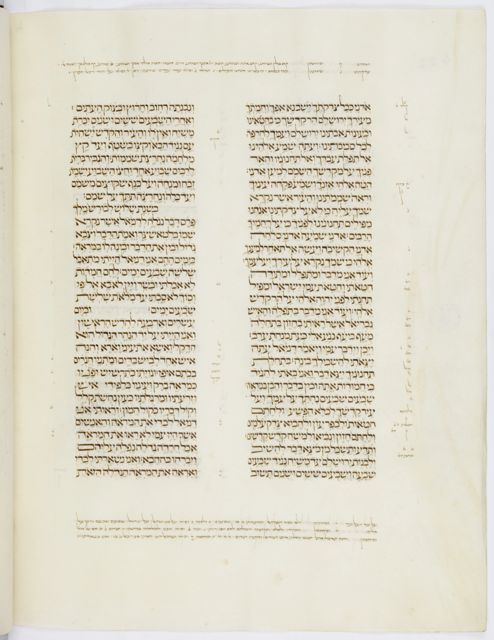

Moses, a master of his art, wrote the text in a beautiful, bold Sephardi script; around it he penned the most delicate micrography, with which he sometimes fashions intricate geometrical shapes:

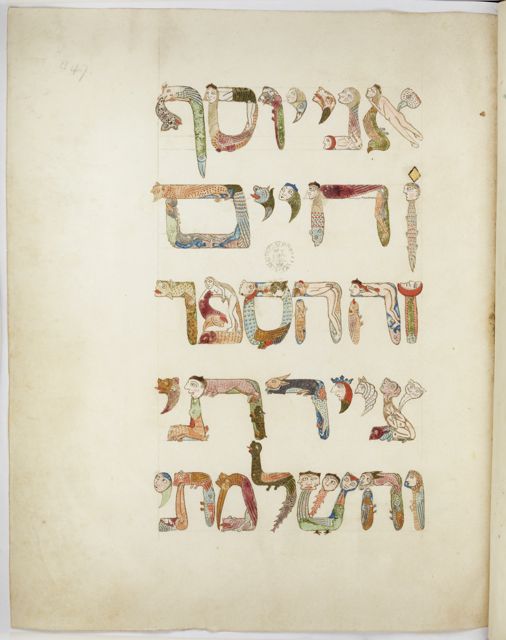

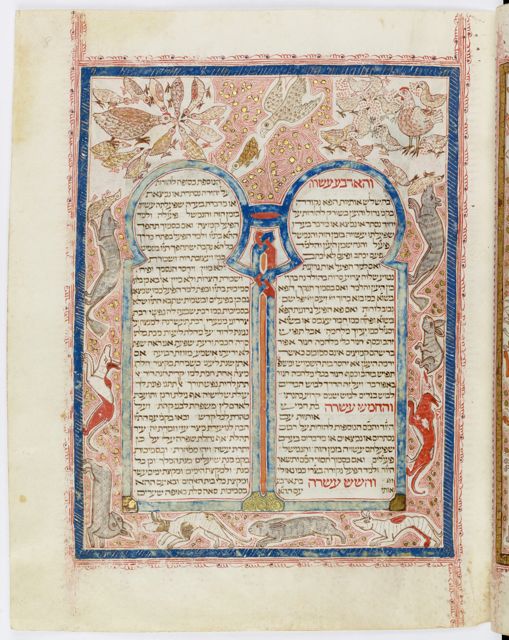

He did not work alone, but in close collaboration with an artist of genius, who on the last page of the manuscript exuberantly signed his name in anthropomorphic and zoomorphic creatures: ‘I, Joseph Ibn Hayyim, illuminated and completed this book.’ In gold and brightly coloured paints Joseph adorned the text with elaborate (pen work), (creatures) of all description, carpet pages, and the occasional biblical scene.

Between them, over a period of perhaps ten months, Moses Ibn Zabarah and Joseph Ibn Hayyim created a masterpiece. Doubtless its owner, the ‘admirable youth’ Don Isaac, was delighted with it, studied it at home, and showed it to his friends and acquaintances with pride. It began its travels in 1492, when the Jews were expelled from Spain. Secure in its distinctive box binding, it may have gone with Isaac di Braga first to Portugal, and from there to North Africa, eventually, almost three centuries after its completion, finding its way to Oxford.

In June 1770 Benjamin Kennicott, biblical scholar and Librarian of Oxford’s Radcliffe Library, told the Radcliffe trustees that ‘it might add considerably to the Ornament of that Library, if it possessed one manuscript of the Hebrew Bible’. He informed them that he had in his hands such a manuscript, ‘very elegant and finely illuminated’, and that it was for sale. The trustees duly purchased the Bible the following April, and it remained the property of the Radcliffe Library until 1872, when it was transferred to the Bodleian. Kennicott could not have made a better choice, for the Bible, now named after him, is one of the finest Hebrew manuscripts in existence. How did he come by it? It had been placed in his hands by the Earl of Panmure, to whom it had been entrusted by its owner, Patrick Chalmers, a Scottish merchant, who had purchased it in Gibraltar. From Gibraltar we can trace the manuscript back to north Africa, and from there to La Coruña in Spain, where it was created.

Our witness is the scribe, who in a colophon at the end of the biblical text signed his name, Moses Ibn Zabarah. He recorded that he finished the work in La Coruña in the 5236th year since the Creation – that is, AD 1476; that he was responsible for copying, checking and correcting the entire text; and that it was made for his patron, the ‘admirable youth, Isaac, son of the late honourable and beloved Don Solomon di Braga’:

The blessed Lord grant that he study it, he and his children and his children’s children throughout all generations … And God enable him to produce many books, in order to fulfil the saying ‘and moreover take care, my son, to produce many books, books without end’. Amen, God grant that it be so.

Moses, a master of his art, wrote the text in a beautiful, bold Sephardi script; around it he penned the most delicate micrography, with which he sometimes fashions intricate geometrical shapes:

He did not work alone, but in close collaboration with an artist of genius, who on the last page of the manuscript exuberantly signed his name in anthropomorphic and zoomorphic creatures: ‘I, Joseph Ibn Hayyim, illuminated and completed this book.’ In gold and brightly coloured paints Joseph adorned the text with elaborate (pen work), (creatures) of all description, carpet pages, and the occasional biblical scene.

Between them, over a period of perhaps ten months, Moses Ibn Zabarah and Joseph Ibn Hayyim created a masterpiece. Doubtless its owner, the ‘admirable youth’ Don Isaac, was delighted with it, studied it at home, and showed it to his friends and acquaintances with pride. It began its travels in 1492, when the Jews were expelled from Spain. Secure in its distinctive box binding, it may have gone with Isaac di Braga first to Portugal, and from there to North Africa, eventually, almost three centuries after its completion, finding its way to Oxford.

The Kennicott Bible

http://bav.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/news/the-kennicott-bible

The Kennicott Bible described by Malachi Beit-Arié

https://youtu.be/DfoIQPOsqCc

http://bav.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/news/the-kennicott-bible

The Kennicott Bible described by Malachi Beit-Arié

https://youtu.be/DfoIQPOsqCc

Item Images

Oxford, Bodleian MS. Kennicott 1: 422v

Oxford, Bodleian MS. Kennicott 1: 447r

Oxford, Bodleian MS. Kennicott 1: 8r

Graphic Elements

Divine Symbol

Oxford, Bodleian MS. Kennicott 1: Divine Symbol - #31918

Oxford, Bodleian MS. Kennicott 1: Divine Symbol - #31919

Oxford, Bodleian MS. Kennicott 1: Divine Symbol - #31920

Specimens

Oxford, Bodleian MS. Kennicott 1

Bodleian Library (Oxford, United Kingdom)

Oxford, Bodleian MS. Kennicott 1: Artist - Square

Bodleian Library (Oxford, United Kingdom)

Oxford, Bodleian MS. Kennicott 1: Main text scribe; Vocaliser; Massorete - Square

Bodleian Library (Oxford, United Kingdom)